Coastal Heritage Magazine

Trailblazers of the Reconstruction Era

With a new National Park Service site planned for Beaufort County, the people who led the way during Reconstruction gain new acclaim.

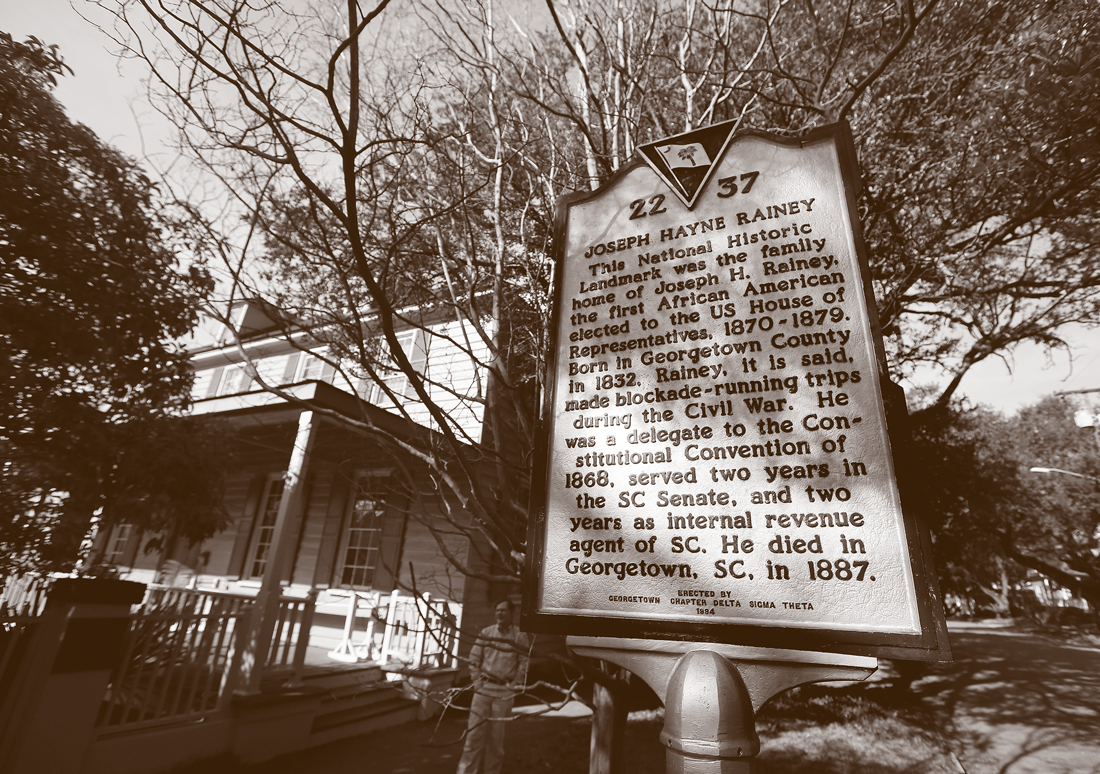

History Abounds. A marker was erected in 1994 at the Georgetown home of Joseph Rainey. A revival of interest in Rainey and other important figures of Reconstruction is expected with the recent announcement of a National Park Service Reconstruction National Monument in Beaufort County, S.C. Photo by Grace Beahm.

Trailblazers of the Reconstruction Era

Robert Smalls pulled off a feat so daring it landed him an audience with President Abraham Lincoln as well as a trip to New York to bolster support for the Union effort during the Civil War.

Frances Rollin Whipper sued a Charleston public transportation company in 1867 for refusing to sell her a first-class ticket because she was black, and won the case.

Laura Towne started a school for former slaves on Saint Helena Island in 1862, just a few months after such an institution would have been illegal, and it’s still a center of the community.

Reverend Richard Cain reinvigorated an African-American church that remains a Charleston icon, and he was a suburban real-estate developer in coastal South Carolina decades before true suburbs arose in the region.

Francis Cardozo was the first African American to hold statewide office in the United States. Joseph Rainey was the first African American to serve in the United States House of Representatives.

Robert Smalls, the most prominent African-American figure in South Carolina during Reconstruction, is celebrated with a sculpture outside Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort, S.C. Photo by Grace Beahm.

These residents of Reconstruction-era South Carolina in the second half of the 19th century lived amazing lives, with plot twists worthy of best-selling novels or blockbuster motion pictures. Yet this is how South Carolina history textbooks referred to their era and accomplishments for the first half of the 20th century:

“The State had a tremendous problem to face in the sudden freeing of thousands of irresponsible, uneducated, unmoral, and, in many cases, brutish Africans. The people of South Carolina felt that they were a danger and that harsh laws were necessary to hold them in bounds.”

That is from History of South Carolina, revised in 1916 by Mary C. Simms Oliphant from the original book written by her grandfather, William Gilmore Simms. The words reflected the ruling class viewpoint in the early 20th century.

The New Simms History of South Carolina, Oliphant’s 1940 update, toned down the rhetoric only slightly. The chapter on the period after the Civil War was titled “Reconstruction—The State’s Darkest Day.”

“The horrors of war were nothing compared to those of this period when Congress was ‘reconstructing’ the State,” it reads, referring to those elected to the state Legislature during Reconstruction as carpetbaggers, scalawags, and negroes. “For eight years, they plundered and robbed the State. … The Congress of the United States kept troops in South Carolina to keep these thieves in power.”

Rather than being celebrated for achievements against great odds, the Reconstruction-era leaders of the newly free black population were ignored individually and pilloried collectively. By the 1970 version of the Oliphant textbook, now titled The History of South Carolina, figures such as Cain, Cardozo, Rainey, and Smalls did merit mentions. The overriding message, however, remained that nothing positive happened during Reconstruction. The next section in the textbook was renamed “The End of a Tragic Era.”

Reconstruction was the historical period born of the emancipation of slaves and the economic and political upheaval of the Civil War. It was marked by a brief period when black residents flexed political muscle reflecting their numbers. The beginning of the end of Reconstruction was the 1876 election, when the Democrats, then the party of the white establishment, used voter intimidation to regain control of state politics. A new state constitution in 1895 further disenfranchised black voters, and the Reconstruction era ended by the turn of the century.

Reverend Abraham Murray, current pastor at the historic Brick Baptist Church on Saint Helena Island, knew little about the region’s rich Reconstruction history when he came to the church 16 years ago. “I was never taught anything good about the period called Reconstruction,” Murray says.

In December 2016, hundreds of history enthusiasts packed Brick Baptist Church at a public meeting to discuss establishing a National Park Service (NPS) site in Beaufort County to commemorate Reconstruction. The meeting was the final official event in a 15-year effort. Barack Obama, in one of his last acts as president in January 2017, designated a Reconstruction National Monument covering four specific locations in Beaufort County—Brick Baptist Church, Darrah Hall at the adjacent Penn Center, the Emancipation Oak at Camp Saxton in Port Royal, and a former firehouse in Beaufort. From interpretive sites at the firehouse and Penn Center, home to the first school for freed slaves in 1862, visitors will be able to learn about the fascinating people, places, and events of the era.

“We live in the world that Reconstruction made, so it’s very important that we grapple with and understand this period in our history,” says Ehren Foley, a historian with the S.C. State Historic Preservation Office. “And we haven’t really had that reckoning yet, and maybe this is our opportunity to do so.”

In the past 50 years, a wave of scholarly books and papers has broadly examined the Reconstruction period, but little of the scholarship on the subject has filtered down to general public knowledge. One solution could be celebrating the amazing characters of Reconstruction, whose stories make history come alive for students of all ages. The following are snapshots of six fascinating people who called South Carolina home during that era.

Robert Smalls (1839-1915)

Robert Smalls has earned more attention than most of South Carolina’s Reconstruction leaders. A school in Beaufort, a U.S. Army ship, and a section of a U.S. Navy training facility have been named in his honor. The new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., features a statue of Robert Smalls that greets visitors entering the area entitled “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom: Era of Segregation 1876-1968.”

Many believe he deserves more acclaim.

Robert Smalls: harbor pilot, politician, and education advocate. Photo Library of Congress.

“I think Robert Smalls was the most consequential South Carolinian who ever lived,” says U.S. Representative James Clyburn, who taught high school history before entering the political arena.

Yet Smalls wasn’t mentioned in many South Carolina history textbooks for much of the 20th century. It’s not because his life was lacking in dramatics. University of South Carolina history professor Andrew Billingsley’s 2007 book “Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families” reads like hard-to-believe fiction.

“He was a brave, intelligent leader in the decade of biracial political democracy in South Carolina, which has not been equaled even to the present time,” wrote Billingsley in the summary of his book. “The struggle he led in the 1895 Constitutional Convention is at least on a par with the struggle for voting rights in the civil rights era of the 1960s.”

Considering where he came from, Smalls’ accomplishments were astounding. He was born into slavery, the son of a house servant of wealthy Beaufort resident Henry McKee. At age 12, Smalls was taken to Charleston to board with a McKee relative. He went to work as a waiter and a lamplighter, with his pay going to McKee. His powerful physique later led to a job loading cargo on the city docks, graduating to jobs as a rigger and a boat pilot. Those skills were critical to the daring event that shaped the rest of Smalls’ life.

Soon after the Civil War broke out, Smalls was pressed into service on the Confederate steamer Planter. Like many in his situation, he longed for freedom. On the night of May 13, 1862, he saw his chance. Confederate officers in charge of Planter left the black crew on the boat and went ashore for the night. After quietly sending for the crew’s family members to come aboard, Smalls pulled Planter away from the dock flying the South Carolina and Confederate flags. Standing tall in the pilothouse, impersonating the ship’s white captain, Smalls guided Planter past multiple checkpoints, including Fort Sumter. Approaching the Union fleet ringing the outer harbor, Smalls raised the white flag of truce and surrendered to the Union Navy.

His daring feat was celebrated in the North, with Union leaders sending Smalls on trips to Washington and New York. He was granted a monetary reward and put in charge of Planter, which became an active Union ship in South Carolina waters. By the end of the war, Smalls earned enough to purchase his former owner’s home, which like many plantation owners’ property was seized to cover unpaid taxes during the war.

Smalls would have deserved fame had he lived a quiet life as a ship pilot or businessman from that point, but he was just getting started. The respect he earned among the black population for his daring act translated into political leadership. He served in the state House of Representatives and Senate and was elected five times to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was an active member of the Constitutional Convention of 1868, which wrote South Carolina’s new governing guidelines.

In the state legislature, he advocated funding for integrated public schools. (Smalls had no formal education before hiring tutors to teach him to read and write as an adult.) In Washington, he advocated for his race and projects in his home state, including a naval base in his district at Port Royal.

As white elites regained power in South Carolina late in the 1870s, they tried to purge the remaining blacks from political offices, often with charges of malfeasance. In 1877, Congressman Smalls was charged with accepting a $5,000 bribe to influence the awarding of a government print contract when he was a state legislator in 1873. He was appealing his conviction when President Rutherford B. Hayes granted him a pardon as part of a political deal that began the downfall of Reconstruction.

After the 1876 election, voter intimidation and new voting regulations made it more difficult for African Americans to gain political office. Yet Smalls remained a force in Beaufort County for the rest of his life. He served portions of three more terms in Congress and in 1895 returned to Columbia to serve on the panel writing a new state constitution. While that document further tightened white leaders’ grip on power, Smalls refused to back down.

“My race needs no special defense, for the whole history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people, anywhere,” he said in addressing the Constitutional Convention. “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Making Connections. Robert Smalls’ legacy is strong in Beaufort, where he lived until his death in 1915. A sculptured bust of Smalls’ powerful countenance stands a few feet from his grave at Tabernacle Baptist Church at 907 Craven Street. His home at 511 Prince Street has been beautifully restored. It’s a private residence and not open to the public, but anyone can peer through the magnolia trees and imagine Smalls strolling from the front door to his job a few blocks away as Collector of Customs. Photo by Grace Beahm.

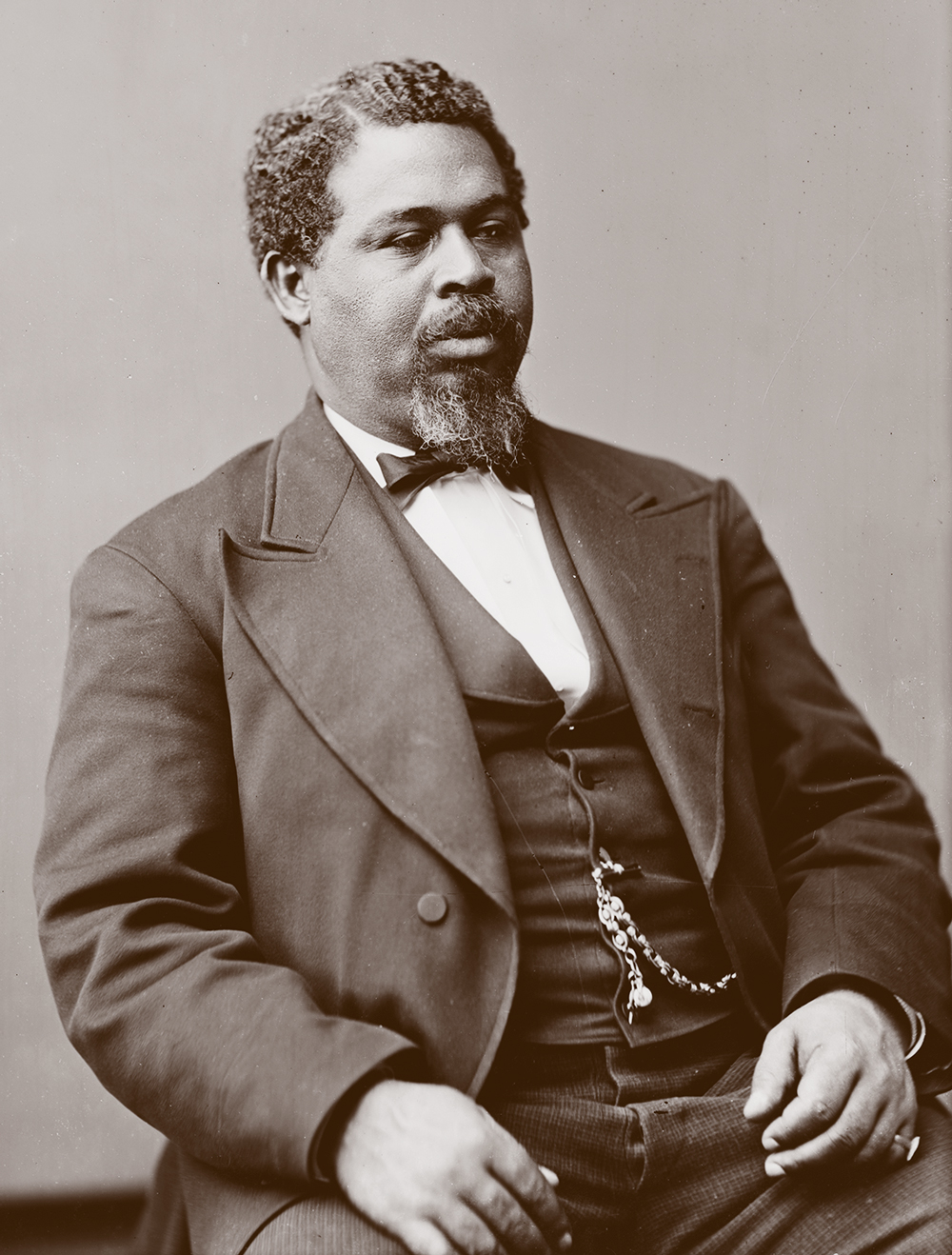

Frances Rollin Whipper (1845-1901)

Eighty-eight years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus in a defining moment of the 20th century Civil Rights movement, Frances Rollin took a similar principled stand in Charleston.

In the summer of 1867, Rollin tried to buy a ticket on the steamer Pilot Boy, which made routine trips from Charleston to Beaufort. Captain W. T. McNelty refused to sell the black woman a first-class ticket, ignoring a recent military order banning discrimination on public conveyances. Like many black South Carolinians, Rollin longed to take advantage of her new rights. Unlike many, she refused to back down when challenged. She took the case to court. In August of 1867, McNelty was found guilty of violating the military order and fined $250.

As historian Willard B. Gatewood, Jr. noted in the January 1991 issue of South Carolina Historical Magazine, McNelty had refused passage to the wrong woman. Rollin was born in 1845 in Charleston, the daughter of free black parents of French and Haitian backgrounds. Her father operated a successful lumber business, and the family was among the city’s black aristocracy. She was educated in Catholic schools in Charleston before being shipped to Philadelphia as war talk heated up to attend the Institute for Colored Youth, a Quaker school. After the war, she returned to Charleston to teach in schools operated by the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association.

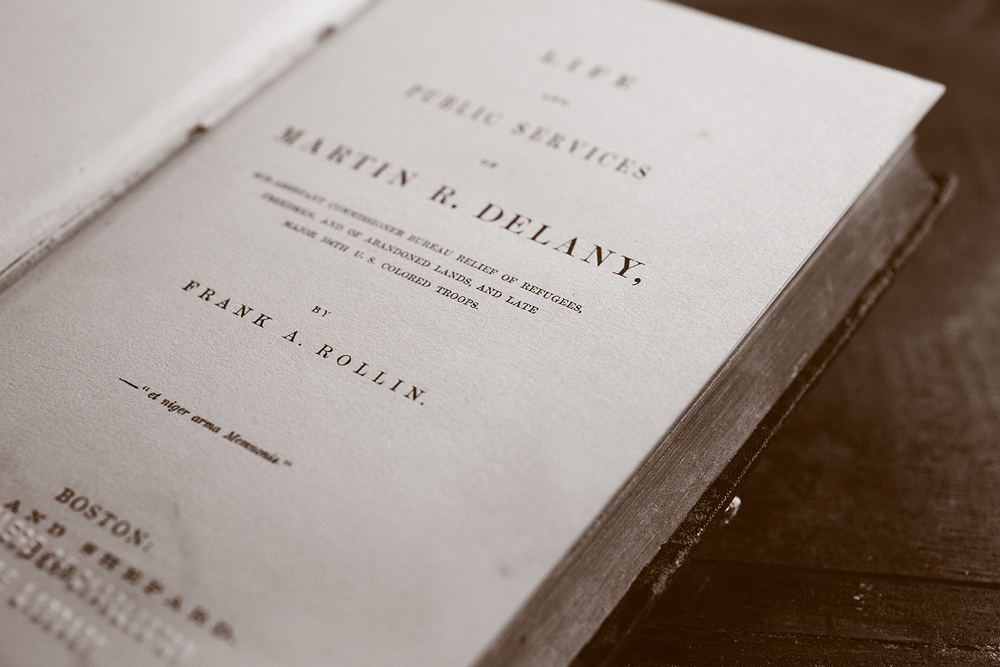

As she pressed her civil rights case in 1867, Rollin sought counsel from Major Martin R. Delany, a high-ranking black military officer with the Freedmen’s Bureau. They became friends, and Delany asked Rollin to write his biography. The end product-Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany—was published under the pseudonym Frank A. Rollin to avoid prejudice against women authors. Some reference books specify it as the first full-length biography written by an African American.

In 1868, Rollin accepted a job in the office of William Whipper, one of the state’s first African-American attorneys and a member of the S.C. House of Representatives from Beaufort County. Whipper, son of a Philadelphia businessman, was recently widowed. Within two weeks of hiring Rollin, Whipper asked her to marry him. Against her family’s objections, she agreed to the union, and they were married a month later.

Rollin Whipper didn’t follow the cultural norm of retreating to the background as the wife of a public official. Through the next decade, she balanced raising the three of her five children who survived infancy with working in her husband’s law office, briefly editing the Beaufort Tribune newspaper, and pushing for women’s suffrage alongside her four sisters. The marriage by all accounts was a rocky one, as William Whipper’s gambling and drinking habits were well known. Late in his career, Whipper moved the family to Washington, D.C. When her husband returned to South Carolina in 1884, Rollin Whipper stayed behind with their children in Washington.

An early example of the working single mother, Rollin Whipper took a job in Frederick Douglass’ Record of Deeds Office in Washington, accepting writing assignments on the side to help make ends meet. Her three children all attended college. One daughter became a nurse and teacher, another earned a degree in medicine and started a home for unwed mothers in Washington, and a son enjoyed a long career as a stage and screen actor.

Shortly before Rollin Whipper’s death, she was contacted by Daniel Murray for details to include in a biography on her in the Encyclopedia of the Colored Race. Her response revealed her humility. “I thank you sincerely that you deem me worthy to be inscribed among those who have contributed to the progress and uplifting of the race,” she wrote. “I have always classed myself among those who never reached the mark they had in sight.”

Words Endure. Frances Rollin Whipper returned to South Carolina late in life and died in 1901 in Beaufort. Her gravesite, likely in the Wesley United Methodist Church cemetery, is unidentified, and no home in South Carolina is celebrated as the Frances Rollin Whipper house. Thus the best way to make a modern-day connection with her is to read passages from the Martin Delany biography she wrote. It’s available in its entirety online. The Special Collections section of the College of Charleston Addlestone Library has a first edition of the book. Photo by Grace Beahm.

Laura Matilda Towne (1825-1901)

Early in the Civil War, Union troops took control of Beaufort and the nearby sea islands, and plantation owners fled to the interior. Abolitionists in northern states felt the formerly enslaved people left behind deserved an education. Enthusiastic to help, Laura Towne left the comfort of a white, upper-class life in Philadelphia and ventured by ship to Beaufort County and filled the void.

Classes began September 22, 1862 at The Oaks plantation with 41 students—Towne referred to them as scholars in her diary. Attendance rose to 110 by October. Eventually, the growth forced a move a few miles away to the larger Brick Baptist Church, and then in 1865 to a new school built next door with the aid of donors from Pennsylvania. It was called Penn School.

“Our school is a delight,” Towne wrote in an 1877 letter. “It rained one day last week, but through the pelting showers came nearly every blessed child. Some of them walk six miles and back, besides doing their task of cotton-picking. Their steady eagerness to learn is just something amazing.”

Laura Matilda Towne: abolitionist, physician, and educator. Photo Library of Congress, the Robin G. Stanford Collection.

Trained in medicine, Towne also was the only physician in the community for years. She would spend mornings traveling house-to-house to treat sick islanders, and then return to the school and teach in the afternoons. She delivered babies, and taught them a few years later.

Ellen Murray, Towne’s friend from Canada, and Charlotte Forten, a free black Northerner, were the primary teachers in the school’s early years. However, Forten referred to Towne as “the most indispensable person on the place, and the people are devoted to her.”

Towne felt equally enamored of the people. Returning from one of her rare trips to Philadelphia, she wrote in a letter: “It is good to be back where you are really needed.”

After the war, many abolitionists lost interest in the plight of the former slaves. Towne stayed. Through Reconstruction and much longer she fought to keep Penn School afloat with pleas to Northern philanthropists for funds. It was a threadbare life, but the school never closed. Towne finally turned over operation of the school to the leaders of Virginia’s Hampton Institute shortly before her death in 1901.

“Her purpose never failed,” Rupert Sargent Holland wrote in Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne: Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-1884. “And though to friends in the North—think of her isolation, her many privations, her constant struggle to keep her school alive—the sacrifice seemed prodigious, to her it meant happiness, as the work chosen for her hand.”

Church School. Laura Towne’s home at Frogmore Plantation on Saint Helena Island is privately owned. Most of the structures on the Penn Center campus post-date Towne, but the Brick Baptist Church (above) remains. Visitors can peer through the windows and imagine multiple classes of students meeting in its open sanctuary. “We have the noise of three large schools in one room, and it is trying to the voice and strength, and not conducive to good order,” Towne wrote in her diary. Photo by Grace Beahm.

Richard Harvey Cain (1825-1887)

Among the remaining vestiges of Reconstruction in South Carolina are enclaves such as Honey Hill or Sol Legare on James Island, where freedmen built homes near the plantations on which they had been enslaved. Reverend Richard Cain, a Northern clergyman sent to Charleston after the war by the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, felt the freedmen deserved more. They deserved communities created separately from the plantations, places just for them, where they could create their own municipal governments and regulations.

“We know how to serve others… but have not learned how to serve ourselves,” Cain said in 1865. “We have always been directed by others in all the affairs of life: They have furnished the thoughts while we have been passive instruments, acting as we were acted upon, mere automatons.”

Cain and six like-minded entrepreneurs took a railroad excursion in search of the ideal spot for a new black community. They opted for a railroad water stop about 20 miles northwest of Charleston. The group paid $1,000 for 620 acres in 1867, and then subdivided it into four-acre lots set up on a grid of dirt roads. Thus was born Lincolnville, one of South Carolina’s first suburban real-estate developments. Cain went on to many grand accomplishments, but the notion behind Lincolnville—self-sufficiency and social advancement for African Americans—held up as a constant in his life.

Richard Harvey Cain: clergyman, entrepreneur, and Congressman. Photo Library of Congress, Congressional Bicentennial Group.

Born in 1825 to a free black father and a Cherokee mother in Virginia, Cain grew up in Ohio and entered the ministry at the age of 19. In 1865, the AME Church assigned him the task of resurrecting Charleston’s Emanuel AME congregation, which had been shut down by authorities after the 1822 slave revolt led by Denmark Vesey. Emanuel quickly grew and became a force in the community, and additional AME churches sprung up in Charleston, Georgetown, Lincolnville, Marion, Summerville, and Sumter.

Cain preached not only in church but also from the pages of his newspaper—South Carolina Leader, later renamed Missionary Record—and from political pulpits in Columbia and Washington. He helped write the state’s 1868 constitution and served one term in the S.C. Senate and two terms in the U.S. House. Before the Lincolnville land purchase, Cain advocated for the federal government taking $1 million out of the Freedmen’s Bureau budget to purchase former plantations and divide the land for sale to landless poor blacks.

Democrats challenged Cain’s Congressional victory in the heated 1876 election. While he survived that challenge, Cain’s increasingly radical ideas cost him the Republican nomination in 1878 and ended his political career. Cain went on to serve supervisory roles in the AME Church in Texas (where he also co-founded Paul Quinn College) and Washington, D.C., before his death in 1887.

Suburban Legacy. Marble memorials to Richard Cain can be found in Emanuel and Morris Brown AME churches in Charleston. His legacy might be most strong, however, in Lincolnville, where East Cain Street ends a block away from Ebenezer AME Church, built on land he donated. While Lincolnville now has a diverse population, African Americans maintain a majority of elected positions. Photo by Grace Beahm.

Francis Lewis Cardozo (1836-1903)

Francis Cardozo, free child of a white customs worker and a multiracial mother, by the norms of the early 19th century was considered black. However, he was granted privileges many blacks in Charleston lacked. He attended schools set up for the black aristocracy, and he was apprenticed to a carpenter during his teen years.

Hungry for education, Cardozo used earnings from his carpentry work in 1858 to pay for a trip to Scotland, where he enrolled at Glasgow University. He moved on to seminary training at renowned colleges in Edinburgh and London. He later earned a law degree from the University of South Carolina, which briefly was integrated during Reconstruction.

Abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher once referred to Cardozo as “the most highly educated negro in America.” How he used that education—a mixture of preaching, teaching, and political leadership—made him truly special.

Francis Lewis Cardozo: educator, clergyman, and politician. Photo Library of Congress.

Cardozo returned to Charleston in July 1865 to take over operation of the American Missionary Association’s Saxton School, which had been established a year earlier by his brother Thomas. Such was the thirst for education among the newly freed that the school, which started with 400 students, grew to 1,050 students from October through December of 1865. Suddenly, his ministry had found its purpose. “If I can influence and shape the future of this great number [of children], if I can cause them to love and serve Christ, I could not aspire to nobler work,” Cardozo wrote to a friend in 1865.

Saxton School moved to new locations several times as it grew until a donation from Northern benefactor Charles Avery allowed school backers to buy two lots on Bull Street. In 1867, Avery School sprouted on those lots as a grand brick building with arches, cupolas, and piazzas.

As Reconstruction began to remake the state, Cardozo turned over operation of the school to others and pursued another passion—politics. He was among the top black firebrands when leaders gathered in 1868 to rewrite South Carolina’s constitution.

“We have been cheated out of our rights for two centuries, and…I want to fix them in the Constitution in such a way that no lawyer, however cunning or astute, can possibly misinterpret the meaning,” he said at the Constitutional Convention. “If we do not do so, we deserve to be, and will be, cheated again.”

Those words proved prophetic a decade later. But the work of that convention allowed blacks to vote in large numbers for the first time during the 1868 election. Most statewide offices still were won by Northern whites who had descended on South Carolina after the war—the carpetbaggers of later history books—or by Southern whites who had sided with the Union—the scalawags. Cardozo was the exception. Elected as a Republican to the office of Secretary of State, he was the first black to win statewide office in the country. He earned re-election in 1870, then won the more important office of State Treasurer in 1872 and 1874.

Cardozo never stopped advocating for public education. At the Constitutional Convention in 1868, he pushed for integrated schools. He later boasted in a letter to the American Missionary Association that in his first months as treasurer he helped allocate $300,000 to public schools, more than his predecessor had in five years. “I take the deepest interest in the schools, especially for my own race that need them so badly,” he wrote.

As whites regained political control in 1876, Cardozo’s former position of power made him a prime target. In 1877, he was convicted of fraud during his time in office. Offered a pardon, he refused and went to prison in 1878 while appealing his conviction. After seven months behind bars, he accepted a new pardon offer and left the state for Washington, D.C.

“His conviction broke him in wealth and spirit,” wrote University of South Carolina law professor Lewis Burke in a South Carolina Law Review article in 2002. “But worse, the Redeemers made their case to the state, the nation, and to history for many years that the Republicans and the African Americans were corrupt and inferior.”

Still Scholarly. Francis Cardozo left South Carolina in 1878 to take a position with the U.S. Treasury in Washington, D.C. Though he spent only a few years in Charleston, his legacy can be found in the grand brick building at 125 Bull Street, now known as the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. In addition to research rooms and exhibit spaces, Avery features a recreated 19th century social studies classroom complete with wooden desks in neat rows. Photo by Grace Beahm.

Joseph Hayne Rainey (1832-1887)

Born into slavery in Georgetown County in 1832, Joseph Rainey parlayed barbering, a Bermudan exile, and bombastic oratory into his special place in history as the first black man seated in the U.S. House of Representatives.

When Rainey was young, his industrious father earned enough money as a barber to buy his family’s freedom. At age 14, Rainey followed his father’s lead and began cutting hair at the Mills House Hotel in Charleston.

Rainey was conscripted into the Confederate military at the beginning of the war. He was assigned to a ship tasked with slipping through the Union blockade of the Charleston harbor. The blockade-running ships often picked up provisions in Bermuda, where Rainey made connections that allowed him to escape to a new life. He and his wife quickly established successful businesses in the bustling Bermudan port of St. George, she as a seamstress, he as a barber.

Joseph Hayne Rainey: barber, orator, and statesman. Photo Library of Congress.

When the war ended, however, he returned home and took on a role of political leadership among the newly freed black population. He helped write the state’s 1868 constitution and was elected to the S.C. Senate in 1870. When a corruption scandal forced S.C. Representative Benjamin Whittemore from the U.S. House, Rainey won a special election to fill his seat. Sworn in on December 12, 1870, Rainey was the first of his race seated in the House. He was joined a few months later by black congressmen selected in the 1870 general election, including fellow South Carolinians Robert De Large and Robert Elliott.

If he had come along 150 years later, Rainey would have been a media sensation. With chiseled facial features and bushy pork chop sideburns, he spiced his eloquent speeches with theatric flair. News reports praised his rare melding of courtesy and aggression. He fought for enforcement of new civil rights regulations, not only on the floor of Congress but in the real world. He once entered a whites-only hotel in Suffolk, Va., and refused to leave until he was forcibly removed.

Among his most impassioned speeches came in reaction to the Hamburg riots, when white men incited by South Carolina Democratic party leaders confronted black militia members parading near Edgefield in July 1876. Part of a pattern of violence aimed at suppressing black votes, the showdown resulted in the deaths of one white man and six black men. No white men were prosecuted in the case.

“In the name of my race and my people,” Rainey said, “in the name of humanity, in the name of God, I ask you whether we are to be American citizens with all the rights and immunities of citizens or whether we are to be vassals and slaves again? I ask you to tell us whether these things are to go on, so that we may understand now and henceforth what we are to expect.”

Past Preserved. After Joseph Rainey lost his Congressional seat in the heated 1878 election, he held jobs in South Carolina and Washington, D.C., before his death in Georgetown, S.C., in 1887. His home at 909 Prince Street has been restored by the Camlin family as a private residence. Its “single house” architectural style is less showy than many neighboring structures, but the high-ceilinged parlor, with original mantel and pine floors, feels like a space where such an accomplished man would have lived. Photo by Grace Beahm.

History Needs Heroes to Make it Come Alive

Modern historians lament that characters like Robert Smalls, Frances Rollin Whipper, Laura Towne, Richard Cain, Francis Cardozo, and Joseph Rainey were ignored in school textbooks for generations. “For so long, there was this leap in what was taught,” says USC history professor Bobby Donaldson. “There was the Civil War and emancipation, and then there’s a fog, and we ended up in the 20th century.”

These days, South Carolina state K-12 history standards do a better job of reflecting Reconstruction. “White propaganda often characterized the African-American elected officials as ignorant ex-slaves,” one section of those standards states. “Although they were inexperienced in governance, as were many whites, most African Americans who served were literate members of the middle class, many of whom had been free before the Civil War.”

Social and economic upheaval at the end of the Civil War was painful for the white elite, and the later collapse of Reconstruction crushed the hopes of African Americans, says Kate Masur, associate professor of history at Northwestern University. But 150 years later, emotions should have calmed enough to allow examination of a period that redefined the country.

Renewed Interest. History tours in Beaufort, S.C., already stop to admire Robert Smalls’ house. Increased attention to Smalls and others from the Reconstruction era is on the way. Photo by Grace Beahm.

“Anniversaries give us a great opportunity to talk about things,” Masur says. “It is important to engage with pasts that bring people into uncomfortable conversations. Maybe they cause people to reflect on problems, rather than triumphs.”

The Reconstruction National Monument will be a huge step in that process. The National Park Service (NPS) created a thorough study of the period, which it considers lasting from 1861 through 1898, and posted a web page devoted to the new monument.

“The presidential designation of the Reconstruction Era National Monument provides the National Park Service with an opportunity to highlight the triumph, success, and promise of freedom to formerly enslaved African Americans,” says Michael Allen, the NPS community partnership specialist who coordinated the effort to gain monument status.

Several organizations have increased efforts to explore and recognize the era. The S.C. Department of Archives and History and the State Historic Preservation Office included 38 Reconstruction sites in African American Historic Places in South Carolina, published in 2015. The S.C. African American Heritage Foundation incorporated those sites into a teacher’s guide with lesson plans.

The Historic Columbia Foundation in 2014 focused the Woodrow Wilson Family Home’s historical displays on Reconstruction. The president spent a portion of his teenage years in Columbia during the early 1870s. McLeod Plantation Historic Site on James Island opened to the public in 2015 with panels describing its use during and immediately after the Civil War. “When we speak with visitors, what strikes us is not only the lack of knowledge about Reconstruction, but the thirst for knowledge about it,” says Shawn Halifax, coordinator of historical interpretation for Charleston County Park and Recreation Commission, which manages the McLeod facility.

The Reconstruction story also will be a component of the new International African American Museum, set to open in Charleston in 2019. Michael Boulware Moore, the museum’s CEO and the great-great grand-son of Robert Smalls, was among the crowd at the Brick Baptist Church speaking in favor of a National Park Service Reconstruction site.

“There’s an upswell of interest in Reconstruction, and this will be an important piece of that,” Moore says. “It’s so important that all young people have heroes to look up to, and this will bring the heroes from that period to life.”

Sidebar

South Carolina’s Seven Constitutions

South Carolina has had seven constitutions, including four in the second half of the 19th century that marked tremendous changes of course and set the tone for the Reconstruction era in South Carolina.

Constitution of 1776: Adopted before the Declaration of Independence. Set up a new system of government, including a General Assembly, with state president and vice president selected by legislators.

Constitution of 1778: Created state Senate. Governor and lieutenant governor replaced president and vice president.

Constitution of 1790: First document created by an elected convention, with minor changes in government structure.

Constitution of 1861: With the Ordinance of Secession passed late in 1860, state leaders tweaked the 1790 document to allow for withdrawal from the Union.

Constitution of 1865: Forced to come up with a new constitution to re-enter the United States. Abolished requirement to own property to be eligible for public office. Didn’t include voting rights for blacks.

Constitution of 1868: Forced again by the federal government to rewrite the document. Created by a convention of delegates from throughout the state, including many blacks. Gave all men the right to vote. Called for public education for all.

Constitution of 1895: Product of a constitutional convention called for by Democratic Party leaders. Voting eligibility regulations disenfranchised many blacks. Legislative changes in 1950 and 1969 loosened those restrictions.

Reading and Websites

Billingsley, Andrew. Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families. University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

Black Americans in Congress, U.S. House of Representatives.

Burke, W. Lewis, Jr. “Post-Reconstruction Justice: The Prosecution and Trial of Francis Lewis Cardozo.” South Carolina Law Review, Winter 2002.

Drago, Edmund L. Charleston’s Avery Center: From Education and Civil Rights to Preserving the African American Experience. The History Press, 2006.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. HarperCollins, 2002.

Gatewood, Willard B., Jr. “The Remarkable Misses Rollin: Black Women in the Reconstruction South Carolina.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, January 1991.

Hampton, Christine W., and Rosalee W. Washington. The History of Lincolnville, South Carolina. CreateSpace, 2007.

Holland, Rupert Sargent, Ed. Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne: Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-1884. Cambridge, 1912.

National Park Service: Reconstruction Era, National Monument South Carolina.

Packwood, Cyril Outerbridge. Detour—Bermuda, Destination—U.S. House of Representatives: The Life of Joseph Hayne Rainey. Baxter’s Ltd., 1977.

Powers, Bernard E., Jr. Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822-1885. The University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Rollin, Frank A. (Frances). Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany. Lee and Shepard, 1883.

S.C. African American Heritage Foundation. A Teacher’s Guide to African American Historic Places in South Carolina.

S.C. Department of Education, Eighth-Grade History Standards, 2016.

Simms, William Gilmore (revised by Mary C. Simms Oliphant). The History of South Carolina. The State Company, 1916.